What a Wine Grape Idea

Can Humboldt County's wine industry fill the green void?

By WIL FRANKLIN | April 17, 2004 | North Coast journal

The Humboldt County economy has been based on a cycle of boom and bust from its inception. From the time the gold rush first drove settlers through the redwood curtain to the timber and fishing industries, Humboldt County has always adapted and survived after economic crashes. Today, Humboldt gets by in no small part due to a marijuana bubble. Many Humboldtians already believe this bubble is starting to shrink and, with legalization likely, poised to burst. The cause and effects are many and debatable, but most citizens can agree that some economic shrinkage is likely in a post-legalization world. Rather than worry about the cause and effect, I would like to look forward at how Humboldt County can adapt, and even grow from this uncertain future.

The Humboldt wine industry is already growing and poised to mushroom thanks to the perfect storm coalescing around water resources, climate change and available land. I believe it's time to take a serious look at how Humboldt might capitalize on sustainable agriculture as an economic cornerstone. Marijuana is likely to remain part of that equation, but other crops will have to take up some slack. Unlike marijuana, grapes are perennials living up to 100 years for some varietals. Once established, quality wine grapes need very little to no irrigation on many of the soil types suitable for grape growing locally. By definition, this is a more sustainable crop.

Planting vineyards is part of Humboldt's solution. However, conventional wisdom claims we cannot produce world-class wine grapes here. The climate is too variable or too wet or too something. Yet, none of these claims are supported by data. When comparing measures of heat accumulation, length of growing season, climatic variability, and rainfall patterns, Humboldt is remarkably well suited to growing quality grapes. It seems conventional wisdom is wrong. Perhaps, Humboldt is not known for grapes for the simple reason that other more lucrative crops are easier to grow. If that incentive changes, as seems likely, can Humboldt adapt and become a world-class winegrowing region?

In my opinion, Humboldt is not only well suited for wine grape growing, it can do so more sustainably using less resources and leaving a smaller carbon footprint than other areas. The drought in California puts a very fine point on my claim. Sonoma, Napa and the Central Coast wine regions of California all face catastrophic water shortages. Water costs are not only soaring, water rights are vanishing all together. Yet, Humboldt has no such problem, even in this drought year.

But, you may ask, does Humboldt really have the qualities of a fine wine growing region? As that question is complex and debatable, let's just ask whether or not we can rule it out. If a necessary characteristic is lacking altogether, then surely we can end the debate. Let's take a look at the metrics of fine winegrowing regions, one by one.

Wine Grapes and Heat

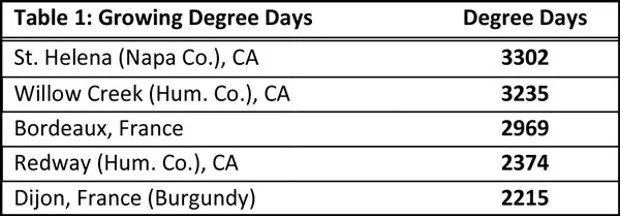

Everyone can agree that grapes will not reach sufficient ripeness if the growing season is too short or too cold. Growing Degree Days (GDD) is an agricultural measure that takes into account length of growing season and accumulated heat over that season. It is measured by the number of hours in a growing season that stay over 50 degrees, below which ripening stops.

If one looks at the Growing Degree Days of the famous wine region of Bordeaux, France, we see the seasonal average falls around 2,969 hours over 50 degrees, while the GDDs for Willow Creek are 3,235, according to the Global Historical Climate Network. This is just right for the heat-loving varietals like Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot and Syrah that are showing quite well in the Klamath-Trinity River Valley running from Willow Creek up to Orleans. And Southern Humboldt has already proven that it can produce world-class red and white wine in the mold of Burgundy, France.

What about Willow Creek, Hoopa and Orleans where there is a growing number of vineyards? Growing Degree Days for Willow Creek are 3,235, while Orleans fall around 3,333. Maybe this is too hot? Yes, perhaps for Pinot Noir, but let's compare this to Napa and Bordeaux, where the likes of cabernet sauvignon, merlot and syrah are typically grown, just as they are out in the Klamath-Trinity River Valley. The GDD for Napa's St. Helena is 3,302 and for Bordeaux the GDD is 2,969, according to data from the GHCN, NOAA and WRCC.

The data suggest that many regions are just right for ripening wine grapes. But never mind those complex indexes; just use the simple tomato test. If you can ripen a juicy, sweet heirloom tomato by August, you can grow just about any wine grape to perfection. And Humboldt is littered with excellent tomato terrain. Moreover, the many different microclimates of Humboldt make it the perfect place for just about any wine grape you would care to grow, just as long as you match the location with the appropriate grape. For example, much of Southern Humboldt has an excellent climate for the pinot noir grapes, while Willow Creek up to Orleans can grow more heat-loving varietals, like merlot, cabernet sauvignon and syrah.

But I don't want to oversimplify — heat accumulation alone does not account for good grape growing. The daily swing between minimum and maximum temperatures is the other half of the heat story. If heat alone was enough there would be great wine regions all over the mid-west, south and eastern seaboard. And they just don't exist. That is due to a myriad of reasons, but not the least is the high nighttime temperatures. Too much heat at night and wine grapes ripen too much and become flabbly, uninteresting wine. Yes, wine is made in all 50 states but, excluding the rare microclimate, none will compete with the Mediterranean climate influenced by the Pacific Ocean, which cools the inland valleys of California to the delight of wine lovers worldwide.

Again, Humboldt is in a sweet spot. Comparing minimum and maximum temperatures during the growing season shows remarkable similarity to the great winegrowing regions of Napa and France, and Humboldt has even more nighttime cooling, giving its wines brighter acidity and, consequently, more complexity and ageability.

Average Minimum and Maximum Temperatures. Data sourced from GHCN, NOAA and WRCC.

Wine Grapes and Rain

Maybe heat alone does not make a fine grape growing region? Perhaps, Humboldt is just too wet and rainy for good grapes?

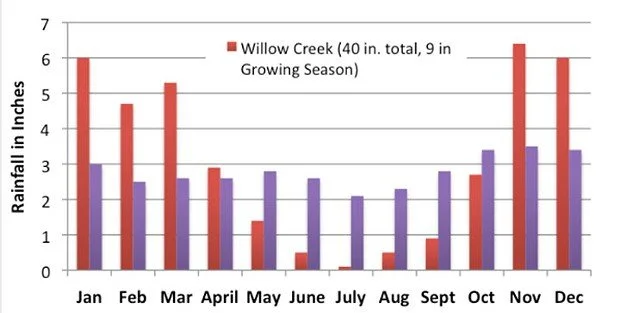

It is true that too much rain and humidity in general could dilute grapes or cause too much mold. Fortunately for us, the grape growing regions of Southern Humboldt and Klamath-Trinity River Valley fall nowhere close to that level. In fact, as a Mediterranean climate, Humboldt's growing season is drier and less humid then the continental climates of Burgundy and Bordeaux. Yes, it is wetter than Napa, but far drier than grape growing regions in France. Rainfall totals very widely over Humboldt's mountainous terrain, with Eureka seeing a yearly total near 40 inches and Honeydew topping off at nearly 75 inches annually. But if you look at when the rain happens, all becomes clear (pun intended). Grapes only grow from April through October and most are harvested by late September to mid-October. There is very little rain during that part of the year in Humboldt.

A continental climate like Burgundy, France, experiences rain all year long, such that they receive far more rain, on average, over the course of a grape growing season. For example, Bordeaux sees around 18 inches of rain, while Willow Creek sees half that much, close to 9 inches. The totals are nearly identical when comparing Burgundy, France, to Redway, according to data from the GHCN, NOAA and World Weather Climate Information.

Growing Degree Days and rainfall patterns are not the only characteristics that influence wine-grape quality, although they are two of the most determinate. The length of the growing season and amount of sunlight will affect ripening. Length of growing season and amount of sunlight is dependent on the geographic latitude of vineyards, the number of freeze-free and cloudy days. Without belaboring the issue, more northern latitudes (all else being equal) give more day-length due to the tilt of the earth's axis. But all else is not equal. Humboldt's interior region, with its nearly cloudless summers (we all know where to go to get away from the summer coastal fog), and its fortunate latitude accumulate more than 120 days of pure sunlight hours between the equinoxes — all of which fall within Humboldt's 160 frost-free days, better known as the growing season. Compare that to the 10 cloudy days on average per month in both Burgundy and Bordeaux over the growing season and they only reach 112 days of pure sunlight hours. Even in a cloudless year, Bordeaux would only see 122 days of sunshine, according to data from the United States Naval Observatory. Humboldt on top yet again!

Rainfall pattern between Mediterranean and Continental climate types. Data sourced from GHCN, NOAA and World Weather and Climate Information (WWCI).

Record setting temperatures, drought and climate change in general beg several important questions. The first is whether Humboldt's climate is too variable. Without bogging down in the numbers, none of these issues are factors for the simple reason that the range of too cool, too short or too long and too hot all fall into those of other world-class winegrowing regions. What you see in Humboldt is vintage variation, but that is wine. Vintages are like the children of a family — they have some commonality, but all are unique and different. Real, hand-crafted wines, all show vintage variation because they are un-manipulated, authentic wines. Be wary of a wine brand that does not show vintage variation — it is likely not wine, but rather manufactured alcoholic beverage loosely based on grapes.

The fact of the matter is that Humboldt does have a slightly cooler winter and slightly shorter growing season compared to Napa. As it turns out, this gives Humboldt one huge advantage — we do not have to install expensive, anti-frost systems, which are usually based on increasingly expensive water or carbon expensive fans. Because the climate in Humboldt's interior forces vines into a deeper dormancy, they don't wake up in the spring until after the threat of frosts. Of course, there are microclimates in Humboldt that do experience late frost, but these are often not fatal and these late frosts have more to do with slope and aspect of a specific vineyard site — not any countywide problem. In fact, Dave Winnett of Winnett Vineyards in Willow Creek, where the vineyard is resting at 900 feet elevation and on a gentle slope, reports no frost damage in over 12 years, except one time on a very small portion of the vineyard that pools cool air. A little damage once in 12 years does not a problem make. The important factor of world-class vineyards is not the macroclimate, as many places worldwide fall into the quality winegrowing range, but rather careful and wise site selection for the vineyard, followed by impeccable care and maintenance. If that is true, Humboldt is rich with potential sites.

Coincidently, the slightly shorter growing season and cooler winter has another important repercussion on winegrowing. Humboldt does not have several vine diseases — including the deadly phylloxera — that are expensive menaces to the south. The fact that Humboldt has less disease and the vineyards do not require expensive anti-frost systems makes winge growing in Humboldt more sustainable with a smaller carbon footprint — utilizing less pesticides, less water, replanting less often and costing less to install and maintain.

The second question that record high temperatures raise is about climate change. It turns out to be a moot point for us. It doesn't much matter if temperatures go up or down because Humboldt is smack in the middle of quality grape growing parameters. There is good winegrowing to the north of us in Washington and Oregon, and there is good winegrowing to the south of us in Sonoma and Napa counties. Furthermore, the vast range of microclimates in Humboldt and the county's complex geology means Humboldt is littered with perfect hillsides just waiting for the right wine-grape.

Wine Grape Growing Soils

So, Humboldt has a good climate, you say, but what about its soils? Contrary to all the hype and propaganda, soils have very little to do with wine quality, except in the extremes. World-class grapes grow in sand (Contra Costa County), or stone pebbles (Chateauneuf du Pape, France), or pure fractured slate (the Rieslings of Bacharach, Germany) or just about anywhere in between. What grapes bound for quality wines cannot handle is deep, overly rich soil or greenish-blue, serpentine soils with unbalanced magnesium to calcium ratios. That leaves more soils than anyone could hope for in Humboldt, or anywhere for that matter.

The qualities of soil that do matter are related to a soil's water holding capacity. As long as grapes can receive enough — but not too much — water, either by irrigation or natural water holding capacity, then it doesn't much matter what the grapes are growing in. My point is simply that there exist an enormous variety of soil types that work well and that except in the extreme cases, soil imparts very few flavors and qualities to wine. It is true that a limestone based soil imparts some nice qualities, but these are marginal and subtle, and plenty of other soil types are responsible for world-class wines. In the end, Humboldt has great soils as long as the farmer doesn't plant on serpentine or kill the living microbial community with too many herbicides. Moreover, the mountainous terrain of Humboldt ensures that the soils are rarely too deep for good grape growing. Coincidently, the average rainfall totals in Humboldt charge the soil's water-holding capacity such that many vineyard sites do not need irrigation. This is not the case in Sonoma and Napa, where water cost are soaring. All this bodes well for sustainable winegrowing in Humboldt.

The Wine Business

Finally, the climate and geology of Humboldt is set against a propitious national and global backdrop. According to the Wine Institute that has been recording data since 1934, domestic wine consumption has continued its upward trend to an all-time high of almost 3 gallons per capita annually. Meanwhile, wine consumption of the raising Chinese and Indian middle class is putting pressure on worldwide supplies. Some economic forecasters, like JP Morgan recently reported in the Washington Times, this pressure may even cause a wine shortage in some regions.

In addition, the Santa Rosa Press Democrat reports that real estate prices, lack of available land, water costs and municipal regulations are making it nearly impossible to plant new vineyards in Sonoma and Napa County.

Annual wine sales remain very strong and are, in fact, increasing. In its December 2013 issue, Wine Business Monthly reported that in the four-week period ending Sept. 14, sales of wines priced at more than $20 per bottle grew 15.9 percent; sales of bottles priced between $9 and $11.99 grew 9 percent; bottles priced between $12 and $14.99 saw sales increase 11.4 percent; and sales of bottles priced between $15 and $19.99 grew 8.5 percent.

All these factors indicate that Humboldt County can produce world-class wines and its nascent wine industry is poised to expand. Moreover, it looks like Humboldt can do it more sustainably and with a smaller carbon footprint. Just look at the data, don't listen to conventional wisdom.

Wilfred Franklin is on the board of the Humboldt Wine Association and is the vineyard manager and winemaker for the new Sun Valley Vineyards in Willow Creek. From the central coast of California to the New Jersey shore, he has worked as a winemaker, vineyard manager and a retailer of imported Italian, German and French wines. Find him on YouTube, click here.