Connect with Us

2020 Cabernet Sauvignon - The Terraces

Hello Friends of Trinity River Vineyards,

I wanted to introduce the new 2020 Cabernet Sauvignon, also know as The Terraces. It is sourced from beautifully terraced hillside vineyards in Mendocino. The shallow hillside soils give the resulting wine depth and concentration. It is unabashedly a fruit bomb in the style of big California Cabs. It is full of fresh blackberry, kirsch and ripe currents. It has a hint bay leaf and thyme - followed by caramel and sweet pipe tobacco. The tannins are rich and smooth, but not a dominant characteristic. Just think, fruity, rich and chocolaty. I find the 2020 a bit more elegant and refined compared to the 2019 vintage. A slightly cooler, shorter growing season, combined with more time aging in barrels before bottling, makes the 2020 smoother and more integrated. I always enjoy The Terraces with lamb or beef, but turns out this has been my go to for chocolate dessert pairings when I do winemaker dinners. For more info on hillside vineyards click here to see an educational video.

This wine is a little more pricey so now is a great time to stack New Release discount onto the Member discount for a total of 30% off through April. Just use Purchase Code NEWRELEASE at check out for 10% off. If you are a club member or become one, you will additionally receive your normal 20% discount for a total of 30%.

As always, we do not ship wine until you order online. This is a NO OBLIGATION deal. If you are interested just go online (shop here) and create your own orders. With membership you always receive a 20% discount on any order and with this Spring Sale you can get an additional 10% off using the limited time Purchase Code. It will expire at the end of March.

Best wishes to all. Stay safe and be well. To follow us more closely please see us on Instagram #trinityriverwines facebook.com/trinityrivervineyards and YouTube

Cheers,

Wil Franklin

Viticulturist and Winemaker

Trinity River Vineyards

3160 Upper Bay Rd

Arcata, CA 95521

Phone: (215) 280-0535

http://trinityrivervineyards.com/

Definition of Wine Terroir?

Starting a Dialogue Between the Cannabis and Wine Industries

Definition of Wine Terroir

Expert Editorial | February 22, 2021

Wine Industry Advisor

As a wine-grape grower, winemaker and Humboldt born native, I have a more than passing interest in the idea of terroir. For me, it is the Holy Grail of the art and science of winemaking and grape growing. As a small grower and producer in a small county with small economic base, I can imagine no greater goal than to produce an agricultural product with a unique signature of place that helps diversify our local economy, supports sustainable agriculture, and elevates the brand that is my home.

And now that cannabis is legal, I believe terroir can be very useful, if not essential to a thriving cannabis industry. Moreover, it just might be the key to the long-term health of small, family-owned cannabis farms across California. If cannabis becomes just another consumable “commodity”, economies of scale will likely drive cannabis agriculture to consolidate and strip small rural communities of an important economic base. In other words, terroir in cannabis, can save small producers and growers like it has helped keep small boutique wine producers and growers alive in every part of California.

Simply defined, terroir relates to the effect environment has on wine-grapes. Plants grown in different environments develop a fingerprint or signature of that place. Terroir was originally a wine termed coined by the French to signify the fingerprint of place on a wine, but it can be generalized to any agricultural product. Coffee has terroir. There are clear differences in single origin coffee from Kenya compared to Costa Rica. Cocoa has terroir. Just try a single origin chocolate from Dick Taylor Craft Chocolates and be blown away in the different flavors and mouthfeel. Tobacco, grass-fed beef and cheese all have terroir. So, why not cannabis?

The answer is, of course cannabis can exhibit terroir. But just like most mass-produced agricultural products, most do not exhibit terroir. Dick Taylor carefully crafts single origin chocolate bars that exhibit terroir, but mass-market Hersey chocolate bars.

Terroir can be in agricultural products. But just as easily, the signature of place can be processed or blended out. When these agricultural products become mass-produced commodities, they lose their unique fingerprint of place. In the hands of a conscientious producer however, terroir can be revealed and subsequently used to help distinguish the product from the hordes scrambling to be recognized in a competitive marketplace.

Terroir is about conscientious farming, sustainable practices and proud stewardship of a unique place. And perhaps just as important to the farmers and producers trying to make a living, it is a meaningful and effective marketing strategy leveraging the intrinsic value of place.

The lesson for cannabis is clear. Farm for high yields, with cheap inputs and that type of farming will likely move to the central valley in the hands of consolidated agro-business. If California wine industry is any guide, terroir could be essential to keeping cannabis farming more distributed and in the hands of small farmers. Does terroir really exist in cannabis? How does one grow for terroir?

It’s Not About Wine Grape Clones or Strains

Grape vines, like cannabis, can be grown from seed or vegetatively propagated, in other words, cloned. Clones are key in both products. Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, Zinfandel are all clones, called varietals in the industry. All Chardonnay vines are very similar to one another. They are vegetative clones of one another. However, plant seeds from Chardonnay and they will NOT grow into more Chardonnay. Some offspring may be similar, but most will be wildly different. Same with apples and similarly with cannabis. Different varieties, strains and varietals do arise from growers planting seeds and looking for interesting offspring. But once that special new individual arises, it can only be propagated with 100% fidelity by cloning vegetatively, not from seeds produced by sexual reproduction.

What does cloning versus sexually reproduction have to do with Terroir? Nothing! These are genetic differences. Terroir is not about genetic differences. It’s not about the difference between Pinot Noir and Merlot, it’s about the difference in Russian River Pinot Noir compared to Trinity River Vineyards Pinot Noir grown in the Willow Creek, AVA.

How Is Terroir Expressed?

Unfortunately, environmental fingerprints are subtle and easily covered up by human practices. Over water and fertilize and all you have is a tasteless, bloated grape. Overuse of herbicides results in dead soils, lacking the necessary microbial community that helps extract the unique profile of nutrients in that local soil type. Or on the production side, a winemaker may put a Pinot Noir in a brand-new barrel for too long and all it tastes like is toasted, caramel and vanilla oak. All traces of terroir are erased by those choices. Terroir is elusive. One must seek it out carefully, knowingly, and then make choices to help express it. At the very least, not to cover it up.

Now imagine the same clones of cannabis growing indoor under lights in bags of potting soil versus growing in the sweet California sunshine. By all accounts from growers and consumers, indoor has a unique profile and is different the outdoor cannabis.

But what about a clone of cannabis grown outside in bags of potting soil? What about a clone started in a greenhouse, some lights and then uncovered to finish in the sunshine? What about the million different fertilizers and additives a grower can give their crop? What about the million little choices a grower makes to produce a profitable product ready to capture market share in an ever increasingly competitive consumer space? Where is the “fingerprint of place” behind all these choices? Does it still shine through all these layers of human choices?

As the cannabis industry develops here in California, I hear many of the same terms about clones and terroir being used. As a botanist, farmer, and winemaker, I believe terroir is real. But what does it mean in the context of cannabis? What does in mean for cannabis that is grown for extraction versus flowers? What does it mean for cannabis destined for edible products versus smoking?

Saving Small Farmers and Wine Producers

Cannabis is a new and developing industry. It is deep in the experimentation phase, just beginning to define itself. Let’s hope growers and producers can convince consumers that terroir is real and has value. If placed-based agricultural products don’t have value, I fear cannabis farming culture and economic output will leave the hands of small producers, just as all commodity farming migrates to the cheapest means of production.

One way to counteract this economic reality is to create value in “place”. The wine industry achieved this through the establishment of legally recognized and regulated use of “place-names”. In the United States these “places of origin” are known as AVAs – American Viticultural Areas. They define specific geographic zones that can be used only for wines produced from grapes grown in that region. On a wine label, one might see “Napa Valley”. That means the grapes only came from that area and not the Central Valley. Origin identification first developed in Europe to protect the good name of certain growing areas. Wines from Bordeaux, France were fetching higher prices and suddenly, all wines were being labeled as wine from Bordeaux. The impetus for these regulated “places” were first and foremost about protecting the value of the products coming from these places.

The larger wine industry in general, needs to reflect on their practices. If consumers want cheap soulless wine that requires harmful practices, then is it worth it? And ditto with a mass-market cannabis industry. The cannabis industry would be well to start educating its consumers of the value of “place”. It has helped keep small wine grape growers and producers alive and diverse. Let’s hope wines of terroir and flowers of terroir become the gold standard of agriculture and economic development. It just might be the only way to keep small farmers and producers alive and prosperous.

Follow Wil Franklin on YouTube

Wil Franklin is the vineyard manager and winemaker for the Trinity River Vineyards in Willow Creek, Humboldt County, California and instructor in the Wine Certificate Program at Humboldt State University (now Cal Poly Humboldt). From the central coast of California in San Luis Obispo to New Jersey, he has worked as a biology professor, winemaker, vineyard manager and retailer of imported Italian, German and French wines. He was born and raised in Humboldt and has degrees in Botany and Biology from Humboldt State University (now Cal Poly Humboldt).

What a Wine Grape Idea

Can Humboldt County's wine industry fill the green void?

By WIL FRANKLIN | April 17, 2004 | North Coast journal

The Humboldt County economy has been based on a cycle of boom and bust from its inception. From the time the gold rush first drove settlers through the redwood curtain to the timber and fishing industries, Humboldt County has always adapted and survived after economic crashes. Today, Humboldt gets by in no small part due to a marijuana bubble. Many Humboldtians already believe this bubble is starting to shrink and, with legalization likely, poised to burst. The cause and effects are many and debatable, but most citizens can agree that some economic shrinkage is likely in a post-legalization world. Rather than worry about the cause and effect, I would like to look forward at how Humboldt County can adapt, and even grow from this uncertain future.

The Humboldt wine industry is already growing and poised to mushroom thanks to the perfect storm coalescing around water resources, climate change and available land. I believe it's time to take a serious look at how Humboldt might capitalize on sustainable agriculture as an economic cornerstone. Marijuana is likely to remain part of that equation, but other crops will have to take up some slack. Unlike marijuana, grapes are perennials living up to 100 years for some varietals. Once established, quality wine grapes need very little to no irrigation on many of the soil types suitable for grape growing locally. By definition, this is a more sustainable crop.

Planting vineyards is part of Humboldt's solution. However, conventional wisdom claims we cannot produce world-class wine grapes here. The climate is too variable or too wet or too something. Yet, none of these claims are supported by data. When comparing measures of heat accumulation, length of growing season, climatic variability, and rainfall patterns, Humboldt is remarkably well suited to growing quality grapes. It seems conventional wisdom is wrong. Perhaps, Humboldt is not known for grapes for the simple reason that other more lucrative crops are easier to grow. If that incentive changes, as seems likely, can Humboldt adapt and become a world-class winegrowing region?

In my opinion, Humboldt is not only well suited for wine grape growing, it can do so more sustainably using less resources and leaving a smaller carbon footprint than other areas. The drought in California puts a very fine point on my claim. Sonoma, Napa and the Central Coast wine regions of California all face catastrophic water shortages. Water costs are not only soaring, water rights are vanishing all together. Yet, Humboldt has no such problem, even in this drought year.

But, you may ask, does Humboldt really have the qualities of a fine wine growing region? As that question is complex and debatable, let's just ask whether or not we can rule it out. If a necessary characteristic is lacking altogether, then surely we can end the debate. Let's take a look at the metrics of fine winegrowing regions, one by one.

Wine Grapes and Heat

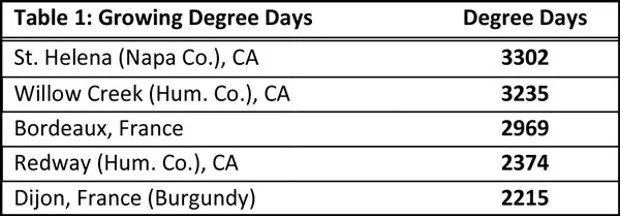

Everyone can agree that grapes will not reach sufficient ripeness if the growing season is too short or too cold. Growing Degree Days (GDD) is an agricultural measure that takes into account length of growing season and accumulated heat over that season. It is measured by the number of hours in a growing season that stay over 50 degrees, below which ripening stops.

If one looks at the Growing Degree Days of the famous wine region of Bordeaux, France, we see the seasonal average falls around 2,969 hours over 50 degrees, while the GDDs for Willow Creek are 3,235, according to the Global Historical Climate Network. This is just right for the heat-loving varietals like Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot and Syrah that are showing quite well in the Klamath-Trinity River Valley running from Willow Creek up to Orleans. And Southern Humboldt has already proven that it can produce world-class red and white wine in the mold of Burgundy, France.

What about Willow Creek, Hoopa and Orleans where there is a growing number of vineyards? Growing Degree Days for Willow Creek are 3,235, while Orleans fall around 3,333. Maybe this is too hot? Yes, perhaps for Pinot Noir, but let's compare this to Napa and Bordeaux, where the likes of cabernet sauvignon, merlot and syrah are typically grown, just as they are out in the Klamath-Trinity River Valley. The GDD for Napa's St. Helena is 3,302 and for Bordeaux the GDD is 2,969, according to data from the GHCN, NOAA and WRCC.

The data suggest that many regions are just right for ripening wine grapes. But never mind those complex indexes; just use the simple tomato test. If you can ripen a juicy, sweet heirloom tomato by August, you can grow just about any wine grape to perfection. And Humboldt is littered with excellent tomato terrain. Moreover, the many different microclimates of Humboldt make it the perfect place for just about any wine grape you would care to grow, just as long as you match the location with the appropriate grape. For example, much of Southern Humboldt has an excellent climate for the pinot noir grapes, while Willow Creek up to Orleans can grow more heat-loving varietals, like merlot, cabernet sauvignon and syrah.

But I don't want to oversimplify — heat accumulation alone does not account for good grape growing. The daily swing between minimum and maximum temperatures is the other half of the heat story. If heat alone was enough there would be great wine regions all over the mid-west, south and eastern seaboard. And they just don't exist. That is due to a myriad of reasons, but not the least is the high nighttime temperatures. Too much heat at night and wine grapes ripen too much and become flabbly, uninteresting wine. Yes, wine is made in all 50 states but, excluding the rare microclimate, none will compete with the Mediterranean climate influenced by the Pacific Ocean, which cools the inland valleys of California to the delight of wine lovers worldwide.

Again, Humboldt is in a sweet spot. Comparing minimum and maximum temperatures during the growing season shows remarkable similarity to the great winegrowing regions of Napa and France, and Humboldt has even more nighttime cooling, giving its wines brighter acidity and, consequently, more complexity and ageability.

Average Minimum and Maximum Temperatures. Data sourced from GHCN, NOAA and WRCC.

Wine Grapes and Rain

Maybe heat alone does not make a fine grape growing region? Perhaps, Humboldt is just too wet and rainy for good grapes?

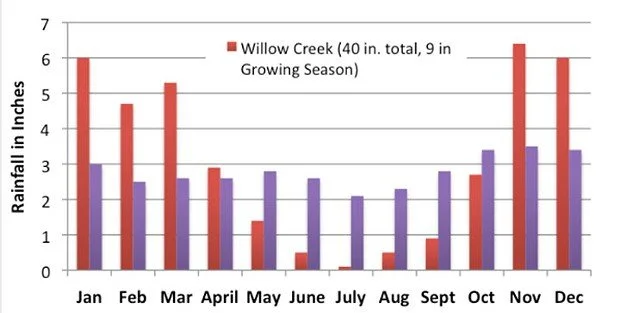

It is true that too much rain and humidity in general could dilute grapes or cause too much mold. Fortunately for us, the grape growing regions of Southern Humboldt and Klamath-Trinity River Valley fall nowhere close to that level. In fact, as a Mediterranean climate, Humboldt's growing season is drier and less humid then the continental climates of Burgundy and Bordeaux. Yes, it is wetter than Napa, but far drier than grape growing regions in France. Rainfall totals very widely over Humboldt's mountainous terrain, with Eureka seeing a yearly total near 40 inches and Honeydew topping off at nearly 75 inches annually. But if you look at when the rain happens, all becomes clear (pun intended). Grapes only grow from April through October and most are harvested by late September to mid-October. There is very little rain during that part of the year in Humboldt.

A continental climate like Burgundy, France, experiences rain all year long, such that they receive far more rain, on average, over the course of a grape growing season. For example, Bordeaux sees around 18 inches of rain, while Willow Creek sees half that much, close to 9 inches. The totals are nearly identical when comparing Burgundy, France, to Redway, according to data from the GHCN, NOAA and World Weather Climate Information.

Growing Degree Days and rainfall patterns are not the only characteristics that influence wine-grape quality, although they are two of the most determinate. The length of the growing season and amount of sunlight will affect ripening. Length of growing season and amount of sunlight is dependent on the geographic latitude of vineyards, the number of freeze-free and cloudy days. Without belaboring the issue, more northern latitudes (all else being equal) give more day-length due to the tilt of the earth's axis. But all else is not equal. Humboldt's interior region, with its nearly cloudless summers (we all know where to go to get away from the summer coastal fog), and its fortunate latitude accumulate more than 120 days of pure sunlight hours between the equinoxes — all of which fall within Humboldt's 160 frost-free days, better known as the growing season. Compare that to the 10 cloudy days on average per month in both Burgundy and Bordeaux over the growing season and they only reach 112 days of pure sunlight hours. Even in a cloudless year, Bordeaux would only see 122 days of sunshine, according to data from the United States Naval Observatory. Humboldt on top yet again!

Rainfall pattern between Mediterranean and Continental climate types. Data sourced from GHCN, NOAA and World Weather and Climate Information (WWCI).

Record setting temperatures, drought and climate change in general beg several important questions. The first is whether Humboldt's climate is too variable. Without bogging down in the numbers, none of these issues are factors for the simple reason that the range of too cool, too short or too long and too hot all fall into those of other world-class winegrowing regions. What you see in Humboldt is vintage variation, but that is wine. Vintages are like the children of a family — they have some commonality, but all are unique and different. Real, hand-crafted wines, all show vintage variation because they are un-manipulated, authentic wines. Be wary of a wine brand that does not show vintage variation — it is likely not wine, but rather manufactured alcoholic beverage loosely based on grapes.

The fact of the matter is that Humboldt does have a slightly cooler winter and slightly shorter growing season compared to Napa. As it turns out, this gives Humboldt one huge advantage — we do not have to install expensive, anti-frost systems, which are usually based on increasingly expensive water or carbon expensive fans. Because the climate in Humboldt's interior forces vines into a deeper dormancy, they don't wake up in the spring until after the threat of frosts. Of course, there are microclimates in Humboldt that do experience late frost, but these are often not fatal and these late frosts have more to do with slope and aspect of a specific vineyard site — not any countywide problem. In fact, Dave Winnett of Winnett Vineyards in Willow Creek, where the vineyard is resting at 900 feet elevation and on a gentle slope, reports no frost damage in over 12 years, except one time on a very small portion of the vineyard that pools cool air. A little damage once in 12 years does not a problem make. The important factor of world-class vineyards is not the macroclimate, as many places worldwide fall into the quality winegrowing range, but rather careful and wise site selection for the vineyard, followed by impeccable care and maintenance. If that is true, Humboldt is rich with potential sites.

Coincidently, the slightly shorter growing season and cooler winter has another important repercussion on winegrowing. Humboldt does not have several vine diseases — including the deadly phylloxera — that are expensive menaces to the south. The fact that Humboldt has less disease and the vineyards do not require expensive anti-frost systems makes winge growing in Humboldt more sustainable with a smaller carbon footprint — utilizing less pesticides, less water, replanting less often and costing less to install and maintain.

The second question that record high temperatures raise is about climate change. It turns out to be a moot point for us. It doesn't much matter if temperatures go up or down because Humboldt is smack in the middle of quality grape growing parameters. There is good winegrowing to the north of us in Washington and Oregon, and there is good winegrowing to the south of us in Sonoma and Napa counties. Furthermore, the vast range of microclimates in Humboldt and the county's complex geology means Humboldt is littered with perfect hillsides just waiting for the right wine-grape.

Wine Grape Growing Soils

So, Humboldt has a good climate, you say, but what about its soils? Contrary to all the hype and propaganda, soils have very little to do with wine quality, except in the extremes. World-class grapes grow in sand (Contra Costa County), or stone pebbles (Chateauneuf du Pape, France), or pure fractured slate (the Rieslings of Bacharach, Germany) or just about anywhere in between. What grapes bound for quality wines cannot handle is deep, overly rich soil or greenish-blue, serpentine soils with unbalanced magnesium to calcium ratios. That leaves more soils than anyone could hope for in Humboldt, or anywhere for that matter.

The qualities of soil that do matter are related to a soil's water holding capacity. As long as grapes can receive enough — but not too much — water, either by irrigation or natural water holding capacity, then it doesn't much matter what the grapes are growing in. My point is simply that there exist an enormous variety of soil types that work well and that except in the extreme cases, soil imparts very few flavors and qualities to wine. It is true that a limestone based soil imparts some nice qualities, but these are marginal and subtle, and plenty of other soil types are responsible for world-class wines. In the end, Humboldt has great soils as long as the farmer doesn't plant on serpentine or kill the living microbial community with too many herbicides. Moreover, the mountainous terrain of Humboldt ensures that the soils are rarely too deep for good grape growing. Coincidently, the average rainfall totals in Humboldt charge the soil's water-holding capacity such that many vineyard sites do not need irrigation. This is not the case in Sonoma and Napa, where water cost are soaring. All this bodes well for sustainable winegrowing in Humboldt.

The Wine Business

Finally, the climate and geology of Humboldt is set against a propitious national and global backdrop. According to the Wine Institute that has been recording data since 1934, domestic wine consumption has continued its upward trend to an all-time high of almost 3 gallons per capita annually. Meanwhile, wine consumption of the raising Chinese and Indian middle class is putting pressure on worldwide supplies. Some economic forecasters, like JP Morgan recently reported in the Washington Times, this pressure may even cause a wine shortage in some regions.

In addition, the Santa Rosa Press Democrat reports that real estate prices, lack of available land, water costs and municipal regulations are making it nearly impossible to plant new vineyards in Sonoma and Napa County.

Annual wine sales remain very strong and are, in fact, increasing. In its December 2013 issue, Wine Business Monthly reported that in the four-week period ending Sept. 14, sales of wines priced at more than $20 per bottle grew 15.9 percent; sales of bottles priced between $9 and $11.99 grew 9 percent; bottles priced between $12 and $14.99 saw sales increase 11.4 percent; and sales of bottles priced between $15 and $19.99 grew 8.5 percent.

All these factors indicate that Humboldt County can produce world-class wines and its nascent wine industry is poised to expand. Moreover, it looks like Humboldt can do it more sustainably and with a smaller carbon footprint. Just look at the data, don't listen to conventional wisdom.

Wilfred Franklin is on the board of the Humboldt Wine Association and is the vineyard manager and winemaker for the new Sun Valley Vineyards in Willow Creek. From the central coast of California to the New Jersey shore, he has worked as a winemaker, vineyard manager and a retailer of imported Italian, German and French wines. Find him on YouTube, click here.

Discovering Wine Again

A California’s winemaker’s journey East

A California’s winemaker’s journey East

Cuizine Magazine, October/November 2002

Conventional wisdom instructs that true fulfilment comes from the journey not the destination. Nevertheless, when I found myself an assistant winemaker in a respected and well-established winery of California, I Again? thought I had "arrived." I had not come to the wine industry directly after years of tutelage and training, but rather propitiously, through the rare and fortunate combination of passion, ability, and luck. Within the very short period of six months, I went from temporary harvest help to assistant winemaker interviewing candidates to be my boss. In the dog-eat-dog world of California winemaking (as with the parallel industry of the Silicon Valley tech-world), turn-over was inevitable and the job market so hectic that any winemaker's warm, half intelligent body would do- if they were willing to sell their soul to the highest bidder.

Straight out of a master’s degree in microbiology, that is exactly what I did. The price? Live in bucolic, rural California, and work twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, for the entire harvest, which typically lasted from mid-September through mid-November, at which point the pace slowed to a mere six days a week until mid-December. Did I care? Not in the least I was being paid to contribute to and learn the most intriguing, utterly consuming, and romantic of human endeavors. Dionysus was not known as the deity of humanity for his community service.

Wine is intimately infused into mankind's very fiber. Throughout history, it has played a defining role in culture, tradition, and commerce. In many parts of the world, wine accompanies two out of three meals, each and everyday. Not coincidentally, it has a symbolic, fi not central role in religious traditions around the world. So, when I moved across the country to Philadelphia to help my wife through graduate school, I despaired that I was leaving the Promised Land. How was I ever to continue the journey I had begun? What could I possibly learn about wine on the East Coast?

In California, the primary value in wine came from the image of a certain lifestyle that reflects one's sophistication, values, and status. Drinking the "right" wine allowed entrance into the elite and making wine catapulted one (deserving or not), into the realm of artistic genius. This image of winemaker as a artist is perpetuated by Oenology Departments worldwide that turn out pseudo-chemists, who consider their burden the heaviest, their training the most rigorous, and consequently their opinions the most important. This is the attitude of the self-aggrandizing winemaker, who sculpts and molds wine into his or her image.

In California, there is no tradition, no long-standing knowledge of place and time, and consequently it is ripe for the winemaker to fill that void with creative declaration. Never mind if the winemaker is trying to place a round peg into a square hole. In California, the goal was to make the biggest, most powerful wine possible. In the warm, dry conditions of the California summer, grapes became very ripe and lent themselves to making powerful wine. Wine was a race to be won, judged on a 100-point scale. Hence, this became the standard to judge all wine. Surrounded by it, drinking it, trading it, buying it, I thus aspired to make it. However, I could not reconcile one small problem.

Grapes turn into wine thanks to microscopic bugs that will do their work whether or not an aspiring "artistic genius" (that would be me) becomes involved. Wine made itself. Winemaking seemed to me to be a misnomer. As far as I could tell, the endeavor should be known as "grape babysitting." If you were good at it, perhaps it could be known as "grape parenting." Wine is in the grape. Good wine is inside good grapes.

The most significant effect a winemaker could have on a wine was first, grow exquisite grapes, then second, ferment them in a clean environment. If this is true, what becomes of the "artistic genius- es" inhabiting the renowned cellars of California and for that matter, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, and even much of Europe?

I had no idea that the path on which I had embarked would lead to entirely novel revelations about the very meaning of wine. Apparently, it was not just a product to "sculpt" in the image of one's own egocentric model or worse, just another mass-produced trinket marketed to the masses. Rather, wine can simultaneously be a beloved pastime and statement of the ultimate, intrinsic value of place and tradition. What in Apollo's name is "ultimate intrinsic value?" And what does it have to do with wine? Hear me out...

Transplanted to Pennsylvania, just outside of Philadelphia, I did what any wine lover in a virtually "dry" state would do; I drove to New Jersey to buy wine (this may seem like a self-indictment; therefore, I invoke poetic license and take the fifth). I soon came across a small, but well-respected wine shop that only carried imported French, Italian, and German wines.

I asked the manager, in a knowing, but unassuming way, "Could you help me find a big Burgundy?" Politely he informed me; "Unlike California style "Burgundy" made from Pinot Noir (red wine from Burgundy, France, is made exclusively from the Pinot Noir grape), true Burgundies are not really considered 'big'. They are known for their aromatic bouquet, finesse, and elegance. In addition, most are the perfect compliment with salmon or a good epoisses cheese."

I froze like a deer in the headlights, "Ah, well. I meant I would like a 'typical Burgundy." Good recovery, I figured, but thank God I didn't tell him I was a winemaker from California. After some more kindly banter and the confession of my true identity, I left with several bottles of very affordable, but "typical" Burgundy to try, if I assured him that I would try them with a good roasted chicken. So, there I sat with my wife over a home cooked meal and real Burgundy. The experience was a revelation. I smelt and tasted baked limestone, dried rose petals, and maraschino cherries, unveiling themselves layer by layer, slowly over the course of our savory meal. Needless to say, I am now a regular customer, not only for the wine I purchase, but also for the ongoing discussions on the background and history of al wines.

What I have discovered, Matt Krammer, Kermit Lynch, and Greg Moore discovered long ago. Wine is much more than just power and mouth-coating, jammy fruit. In the old traditions of Europe, wine was considered a food and consequently it evolved with the gastronomic delicacies of each region. Moreover, each region possessed its own microclimate, soil structure, topography, and native grape varieties. Over centuries and even millennia, with little or no technology, wine was produced that matched certain lifestyles, cuisine, and locations. Each year or vintage brought slightly new variations, such that each new wine was like a newborn child with a personality all its own.

What I had found on the older, more traditional East Coast, was a myriad of unique and authentic wines that were valued for more than just the 98 or 99 points they could fetch. Rather they were prized for their ability to 'evoke "ultimate intrinsic values" of a place and tradition. The wines were not trying to fit some mold that winemakers forced upon the grapes in order to collect accolades from the critics.

Wine, I learned, was an expression of these cultures and traditions, and in that sense, like awork of art. But unlike art, there was no "artist," only humble farmers, with clean manners and long traditions that allowed the expression of place to be unveiled. Places like the Juroncon hidden just north of the Spanish border that makes a lean, acidic, but full-bodied white wine that goes superbly with char-broiled octopus or grilled whole mung fish. And how about Fruili on the Italian-Slovakian border, where the subtle and elegant Tocai Fruiliano makes another delicious white wine served on the hilly terraces overlooking the wind-blown Adriatic Sea. The list goes on and on, but then I would be spoiling all the fun of making your own new discoveries.

This is not to say California or other New World vineyards do not have authentic, delicious wine. Places like Hawkes Bay or Cloudy Bay of New Zealand's northern island produce some very expressive Sauvignon Blanc and Chardonnays. Likewise, the uniqueness of California Zinfandel is continually finding more complexity and nuance and given enough time will equal and in the best cases surpass many European traditions.

The point that I have recently uncovered while on the East Coast, is a simple one. Wine is diverse. Not all wine should try to be alcoholic, mouth-coating fruity bombs. Regional diversity and cultural traditions are another way in which to judge and therefore, enjoy wine. To be honest, it can seem a bit over- whelming. As I've found out, you could spend many lifetimes studying wine and there would still be more to learn. However, the reward really is in the journey, not the destination. I'm learning the lesson first-hand.

Wil Franklin recently moved to the Philadelphia Metro area from California's Central Coast, where he was assistant winemaker at Edna Valley Vineyards. When he's not immersed in the wines at More Brothers Wine Company, he enjoys hiking and gourmet mushroom hunting in the lush deciduous forests of the East Coast. You can find Wil on YouTube, click here and don’t forget to SUBSCRIBE, LIKE and COMMENT.